The Gambler’s Fallacy and Roulette Independence Explained

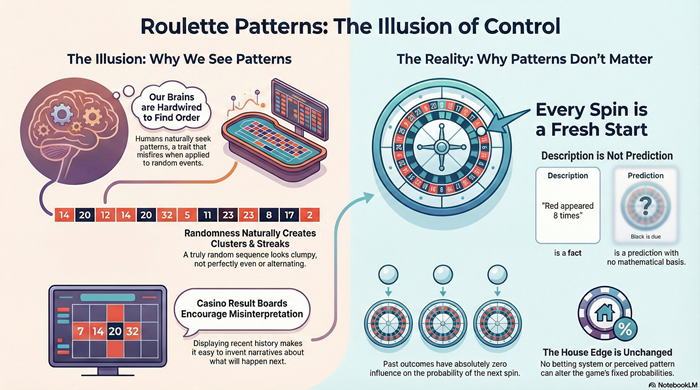

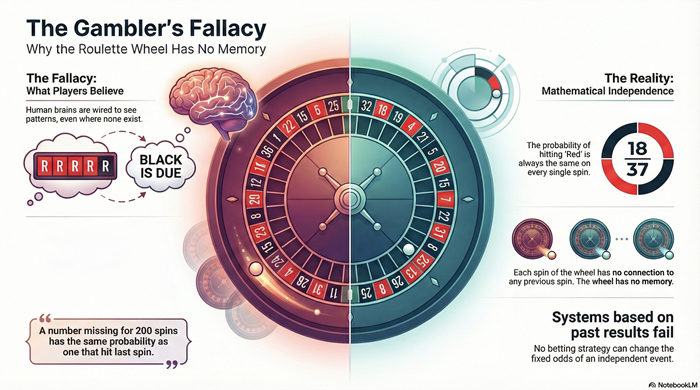

Roulette outcomes often feel connected. Long runs of red seem to invite black. A missing number feels “due.” These intuitions are powerful—and wrong—because they assume the wheel remembers what has already happened.

This article is part of our complete guide on How Roulette Really Works: Odds, House Edge, and Why Systems Fail, which explains roulette odds, house edge, wheel types, and why betting systems fail.

What Is the Gambler’s Fallacy?

The gambler’s fallacy is the belief that past random outcomes change the probabilities of future outcomes. In roulette, it typically appears as the idea that a color, number, or outcome becomes more likely after not appearing for a while.

Common expressions include:

- “Black is due.”

- “Red can’t keep hitting.”

- “Zero hasn’t shown up in ages.”

All of these statements assume a correcting force that does not exist.

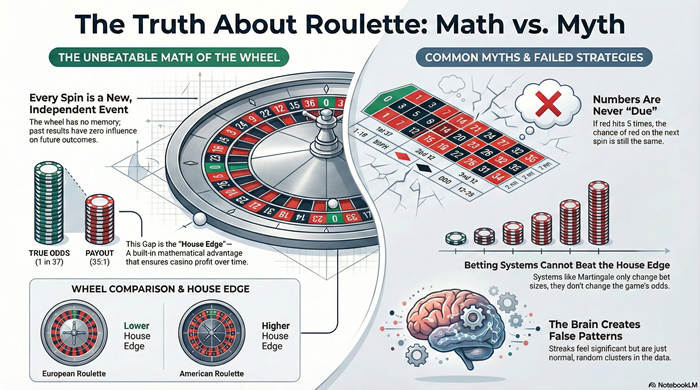

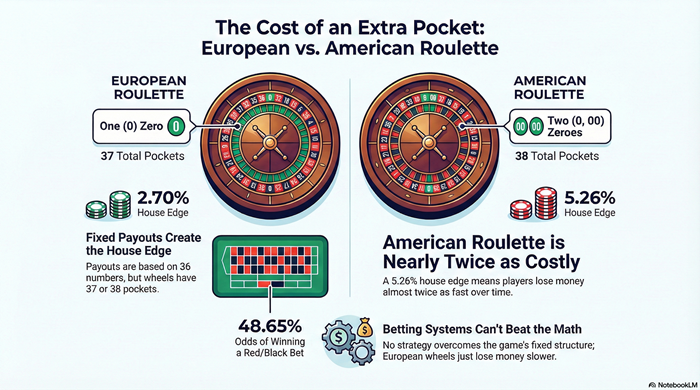

Roulette Spins Are Independent Events

Independence means that each spin of the wheel has no connection to any previous spin.

- The wheel has no memory

- The ball does not compensate for history

- Mechanical randomness does not rebalance outcomes

On a European wheel, the probability of red is the same on every spin: 18 ÷ 37, regardless of what happened before. On an American wheel, it remains 18 ÷ 38.

The probability resets completely after every spin.

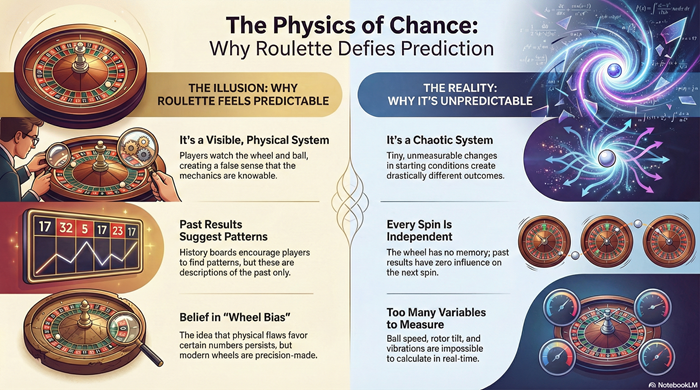

Why Long Streaks Feel Meaningful (But Aren’t)

Humans are pattern-seeking by nature. In environments with real cause-and-effect, this is useful. In independent random processes, it creates false narratives.

Streaks Are Expected

In a long sequence of random events:

- Long runs are normal

- Clusters occur naturally

- “Unusual” sequences happen regularly

A streak of 10 reds is unlikely in isolation, but over thousands of spins, it is not surprising that such streaks appear somewhere.

Seeing a streak does not mean a correction is coming.

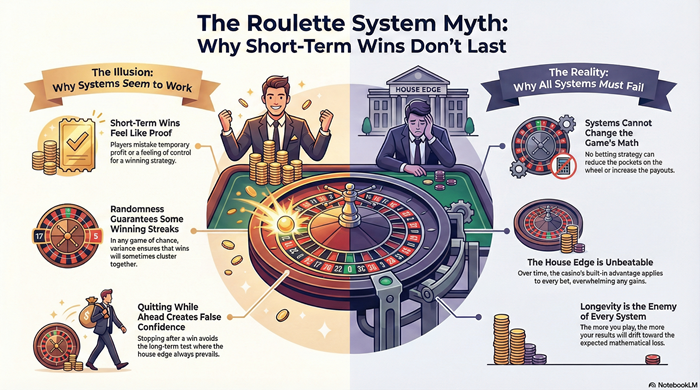

Probability Does Not “Even Out” in the Short Term

A common misunderstanding is that probability enforces balance quickly.

Example belief:

- “After many reds, black must appear to restore fairness.”

Reality:

- Probability balances only over extremely large numbers of trials

- Short-term deviations can persist indefinitely

- Randomness allows imbalance without correction

The law of large numbers describes long-run behavior, not immediate outcomes. It does not force short-term symmetry.

Why “Due” Is Not a Real Concept

For something to be “due,” a mechanism must exist that increases its likelihood based on absence.

Roulette has no such mechanism.

- A number missing for 200 spins has the same probability as one that hit last spin

- Zero does not become more likely because it hasn’t appeared

- The wheel does not track frequency or fairness

“Due” is a psychological label, not a mathematical one.

How Casinos Benefit From the Gambler’s Fallacy

Casinos do not need to encourage the gambler’s fallacy directly. The structure of roulette does it naturally.

- Visible result boards emphasize recent history

- Color sequences invite pattern recognition

- Players interpret randomness emotionally

The fallacy increases engagement and confidence without changing the house edge. Players feel informed, but no information about past spins improves prediction.

Independence vs. Perceived Control

The gambler’s fallacy often pairs with the illusion of control—the belief that awareness, discipline, or timing improves outcomes.

Examples:

- Waiting for a long streak before betting

- Changing bets after losses

- Avoiding numbers that “just hit”

None of these actions affect probability. They only affect how wins and losses are experienced.

Control over betting behavior does not equal control over outcomes.

Why Systems Fail Once Independence Is Understood

Most roulette systems rely, explicitly or implicitly, on the gambler’s fallacy.

They assume:

- Reversion to the mean in the short term

- Increased likelihood after absence

- Predictive value in recent outcomes

Because spins are independent, these assumptions collapse. The system may change bet sizing or timing, but it cannot change expectation.

Once independence is accepted, system failure becomes inevitable, not mysterious.

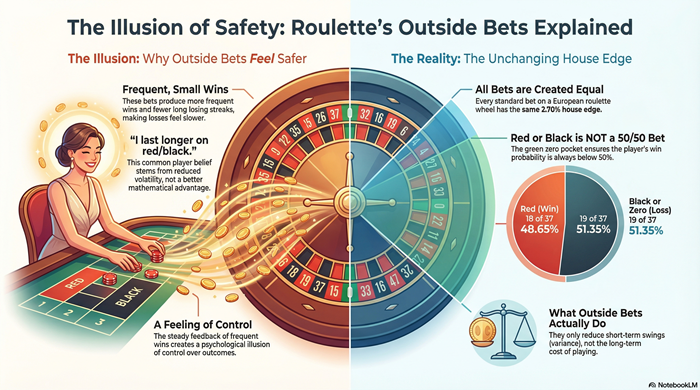

Independence Applies to All Bet Types

Outside bets, inside bets, colors, dozens, and single numbers all obey the same rule:

- Past results do not influence future probabilities

Outside bets feel safer because of lower variance, not because independence weakens over time. Independence applies uniformly across the wheel.

Why This Concept Is So Difficult to Accept

The gambler’s fallacy persists because it conflicts with intuition:

- Human experience expects memory and correction

- Random processes offer neither

- Short-term randomness feels unfair or broken

Roulette feels like it should self-correct. It never does.

Understanding independence is a turning point in understanding roulette itself.

What Understanding Independence Actually Provides

Recognizing independence:

- Removes false expectations

- Explains streaks without mysticism

- Clarifies why systems fail

- Separates emotional comfort from mathematical reality

It does not make roulette predictable. It makes it understandable.

Related Articles in This Roulette Series