How Keno Really Works: Probability, Payouts, and Why “Almost Winning” Feels So Close

What Keno Is (and What It Isn’t)

Keno is a lottery-style numbers game, not a strategic casino game. That distinction is critical, because many misunderstandings begin when keno is treated as something it is not.

Once numbers are chosen and the draw begins, the outcome is governed entirely by probability. There are no decisions to make, no timing to exploit, and no adjustments that influence the result. The system selects numbers, compares them to the ticket, and produces an outcome. Nothing more happens.

What keno is:

- a fixed random process

- a combinatorial probability problem

- a payout structure layered on top of fixed odds

- a game that produces uneven experiences by design

What keno is not:

- a game of skill

- a game of memory

- a game where experience improves outcomes

- a game that adapts to player behavior

The act of choosing numbers creates participation, but not influence. All meaningful interaction ends before the mathematics begins. This is what separates keno from games where decisions affect expectation.

Without this framing, later concepts feel unfair or mysterious. With it, keno becomes easier to understand honestly: not as a contest to solve, but as a mathematical system that behaves consistently over time.

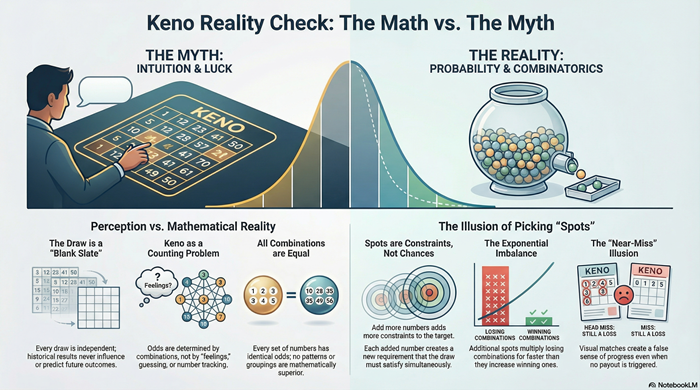

How Keno Draws Work: Independence and Randomness

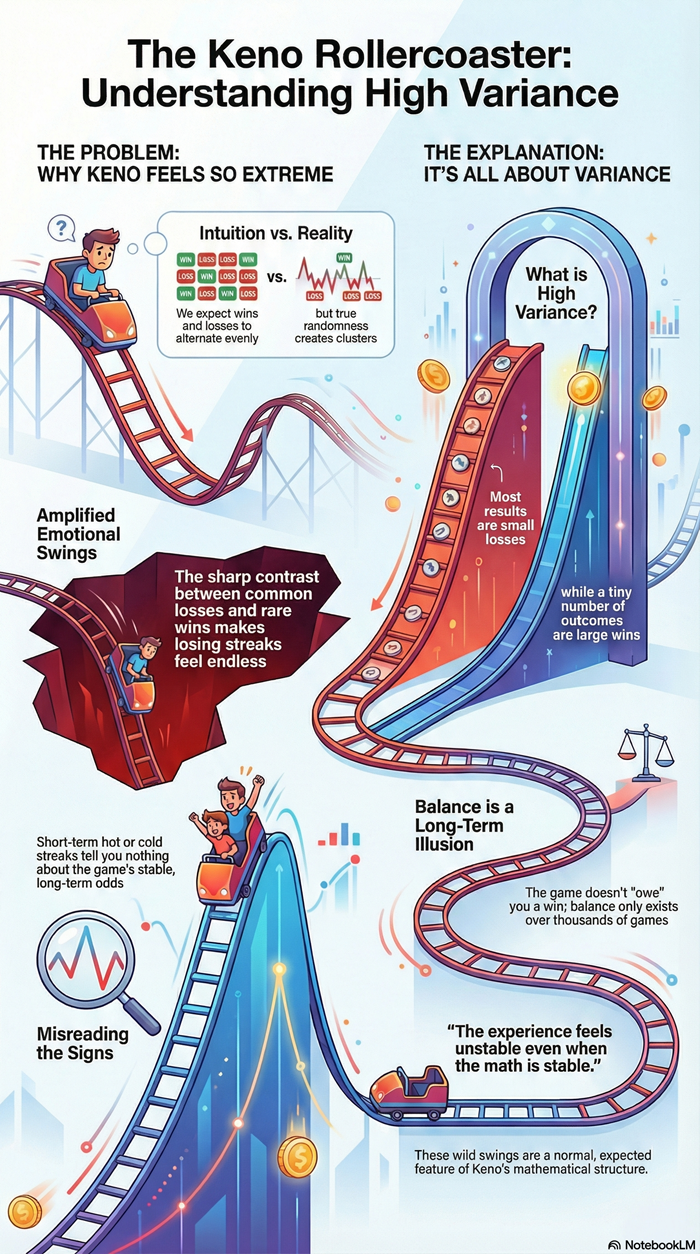

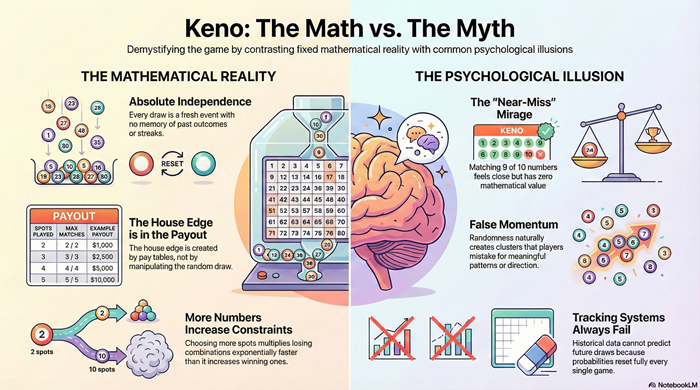

Every keno draw is an independent random event. Independence means the system does not remember previous draws, correct itself, or compensate for streaks.

Past outcomes contain no information about future outcomes. A number that appears frequently is not becoming less likely. A number that has not appeared is not becoming “due.” Probabilities reset fully on every draw.

Randomness does not produce smooth alternation. It produces clusters, gaps, and repetition. These features often feel meaningful, but they are expected behavior, not signals.

Timing does not matter. Playing after a long drought or after a win does not change the next draw. The mechanism repeats the same process each time.

Understanding independence removes the expectation that the game should respond. Once that expectation is gone, many emotional reactions lose their force.

Spot Selection and Combinatorics

A “spot” refers to how many numbers are selected on a ticket. This choice feels flexible, but mathematically it is decisive.

When you choose spots, you are selecting one exact configuration from a massive universe of possible configurations. As spot count increases, the number of possible draw combinations grows explosively, while the number of exact-match combinations grows very slowly.

This imbalance is exponential. Each added number multiplies losing combinations far more than winning ones.

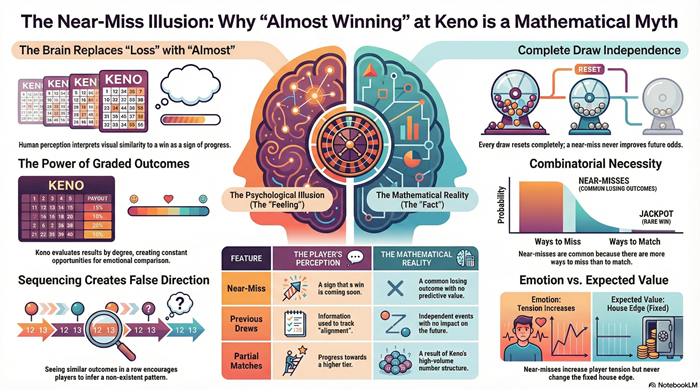

Near-matches are common because exact matches are rare. Missing by one number feels close, but combinatorially it is not special. Closeness has no mathematical value.

Which numbers you choose does not matter. Only how many you choose matters. Once the spot count is set, the probability structure is locked.

Keno Odds: Why More Numbers Don’t Help

Adding more numbers feels like adding opportunity, but it actually adds constraints.

Each additional number becomes another condition that must be met simultaneously. As conditions stack, probability declines sharply. This decline accelerates rather than slowing.

Higher-spot tickets generate more visible matches and more near-misses, which creates the illusion of progress. That activity is visual, not probabilistic.

Seeing many numbers appear does not indicate movement toward success. Each draw starts fresh, and the odds of full alignment remain unchanged.

Keno rewards exact outcomes, not partial effort.

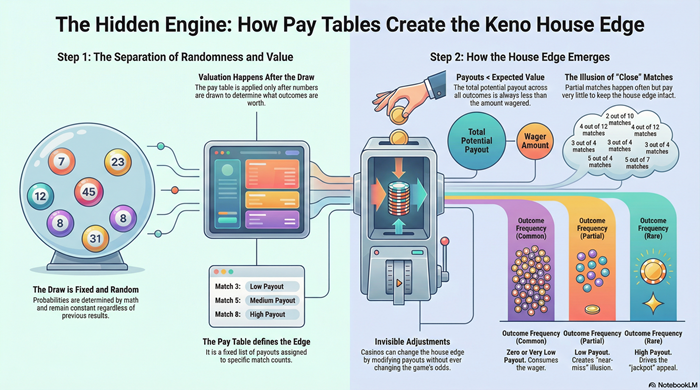

Pay Tables and the House Edge

The house edge in keno does not come from the draw. The draw is fixed and random. The house edge is created entirely by payout structure.

Pay tables assign values to outcomes after the draw has already occurred. These values are designed so that, when weighted by probability, total expected payout is less than the amount wagered.

Frequent outcomes must pay little. Rare outcomes carry most of the payout potential. This structure guarantees a long-term imbalance without requiring any adjustment during play.

Two keno games can look identical yet produce very different long-term results simply by using different pay tables. Once the table is set, expected value is fixed.

Expected Value vs Experience

Expected value describes long-term averages. Experience describes how results arrive.

In keno, these two diverge sharply. Losses are frequent and similar, so they blur together in memory. Wins are rare and emotionally sharp, so they stand out.

This creates a distorted sense of frequency and effectiveness. Experience feels meaningful even when it contradicts expectation.

Expected value does not predict sequence. It describes structure. Experience reacts to timing, memory, and emotion.

Understanding this distinction resolves much of keno’s apparent inconsistency.

Variance: Why Keno Feels So Extreme

Variance describes how unevenly outcomes are distributed around the average. Keno has extremely high variance.

Most draws produce nothing. A small number produce noticeable outcomes. A very small number produce dramatic ones. This creates long dry spells punctuated by sudden wins.

High variance does not change odds or house edge. It changes how results feel.

Extreme swings are not suspicious. They are expected.

The Near-Miss Illusion in Keno

A near-miss feels close to winning without being meaningfully closer.

Keno produces many near-misses because partial overlap is common in large combination spaces. The game displays these overlaps clearly, inviting comparison between what happened and what almost happened.

The brain evaluates similarity, not probability. Outcomes that resemble success are processed differently, even when they are not closer in any mathematical sense.

Near-misses feel personal because the numbers are chosen, even though the draw is blind to that choice.

Why Near-Misses Create False Momentum

Repeated near-misses create the sensation of momentum—the feeling that success is building.

Momentum implies carryover. Keno has none. Each draw resets completely.

The illusion forms because similar outcomes appear close together. The mind interprets sequence as direction, even though randomness has no direction.

False momentum feels earned, but it exists only in perception.

Why Number Systems and Tracking Fail

All keno systems rely on the assumption that past draws contain predictive information. They do not.

Tracking can describe history accurately. It cannot improve future outcomes. Independence prevents accumulation, correction, or learning.

Short-term success is explained by variance, not effectiveness. Over enough draws, the house edge embedded in the pay table reasserts itself.

Systems persist because they feel analytical and disciplined, not because they work.

Why Keno Is Especially Vulnerable to Misinterpretation

Keno produces dense numeric feedback: many numbers, frequent draws, and graded outcomes. This environment strongly invites interpretation.

Personal number choice creates ownership. Graded outcomes invite comparison. Frequent draws encourage short-term narratives.

The game looks analytical without being optimizable. This mismatch makes misunderstanding persistent, even among informed players.

What Understanding Keno Changes

Understanding keno does not change outcomes. It changes interpretation.

Near-misses stop feeling informative. Patterns stop implying intent. Long losses stop feeling abnormal.

Keno becomes what it has always been: a fixed mathematical system producing uneven experiences by design.

Once expectations align with structure, the mystery disappears—not because outcomes become predictable, but because the system finally makes sense.

Related Pages