Why Keno Number Systems and Tracking Don’t Work

This article is part of our complete guide on How Keno Really Works: Probability, Payouts, and Why “Almost Winning” Feels So Close, which explains keno probability, house edge, variance, and why common myths fail.

Introduction

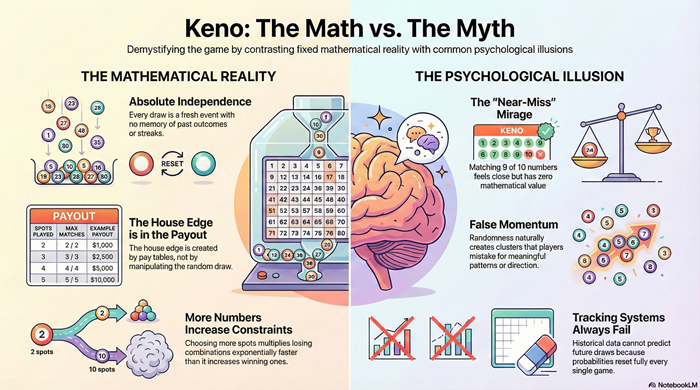

Keno attracts number systems, charts, and tracking methods more than almost any other casino game. Players record results, label numbers as hot or cold, rotate selections, and adjust tickets based on recent history. These approaches feel analytical and disciplined—but they all rely on the same mistaken assumption.

That assumption is that past keno draws contain information about future ones. This article explains why that belief fails, why tracking feels persuasive anyway, and why systems remain compelling even after repeated disappointment.

Why Keno Number Systems and Tracking Don’t Work

What People Mean by “Keno Systems”

Keno systems usually fall into a few recognizable categories. Some track “hot” numbers that appear frequently. Others avoid “cold” numbers that have not appeared recently. Some rotate number sets to increase coverage over time. Others adjust spot counts based on recent outcomes.

Although these methods differ in presentation, they share the same goal: to use past results to influence future ones.

That goal is mathematically impossible in keno.

Why Past Keno Draws Don’t Contain Predictive Information

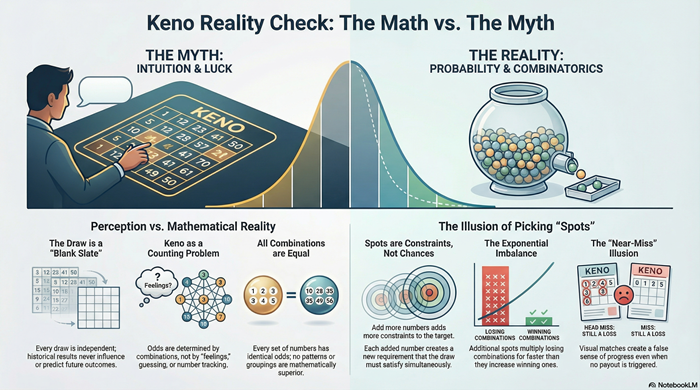

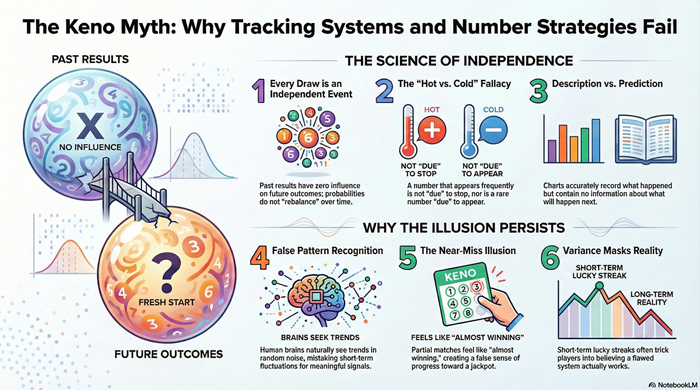

Every keno draw is independent. Once a draw is complete, its numbers have no influence on what happens next.

Independence means probabilities do not accumulate, correct themselves, or rebalance. A number that has appeared many times is not becoming less likely to appear again. A number that has not appeared is not becoming more likely to show up next.

Recording results does not change this. Charts and logs can describe the past accurately, but they cannot extract information that does not exist. The draw mechanism does not reference previous outcomes.

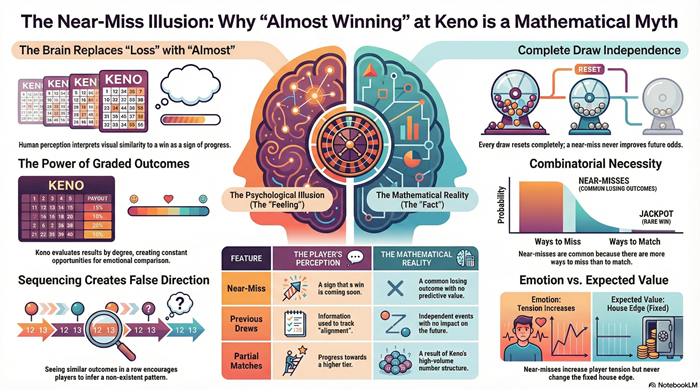

Why Tracking Feels Predictive Even When It Isn’t

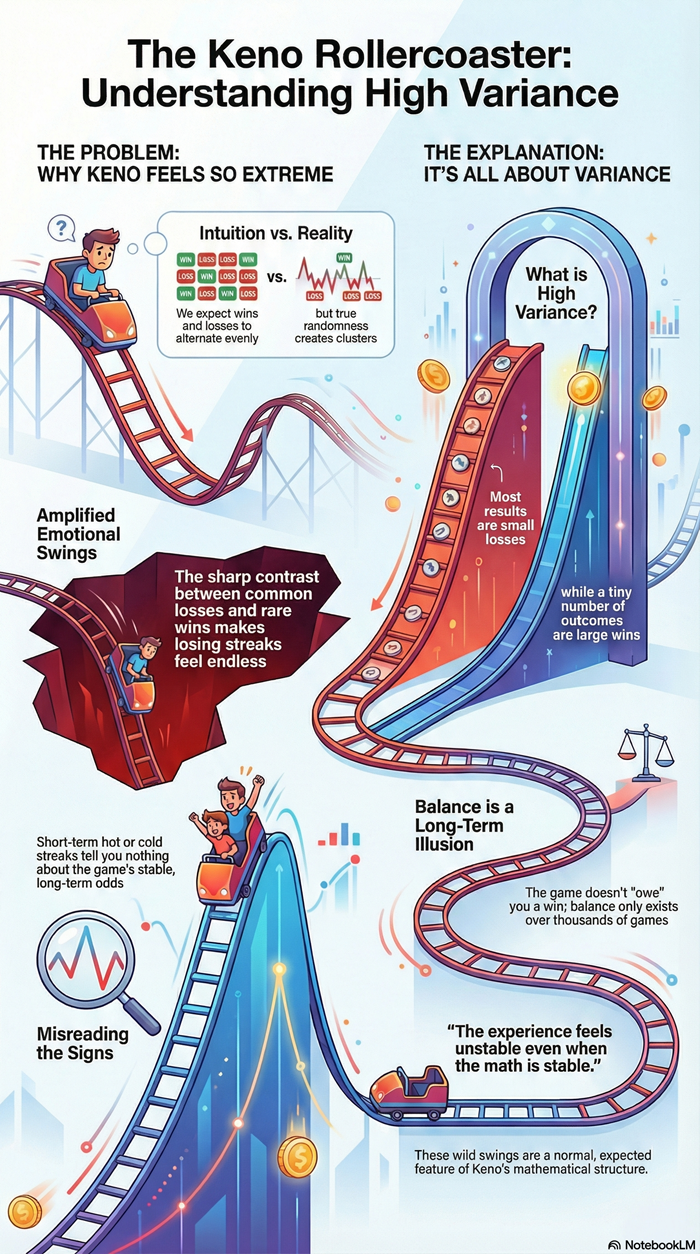

Tracking feels useful because random systems produce uneven distributions in the short term. Some numbers cluster. Others disappear. These fluctuations are normal, but they look meaningful when viewed sequentially.

Human pattern recognition fills in intent where none exists. When a tracked number appears soon after being labeled, the coincidence feels confirmatory. When it does not appear, the absence is easier to forget.

Over time, selective memory creates a narrative that the system “works sometimes,” even though its apparent successes are fully explained by chance.

Why Systems Fail Even When They Seem to Work

Short-term success does not validate a system. In high-variance games like keno, random outcomes will occasionally align with almost any method.

When a system appears to work briefly, variance is masking the underlying expectation. Losses that follow are often attributed to bad timing rather than to structural failure.

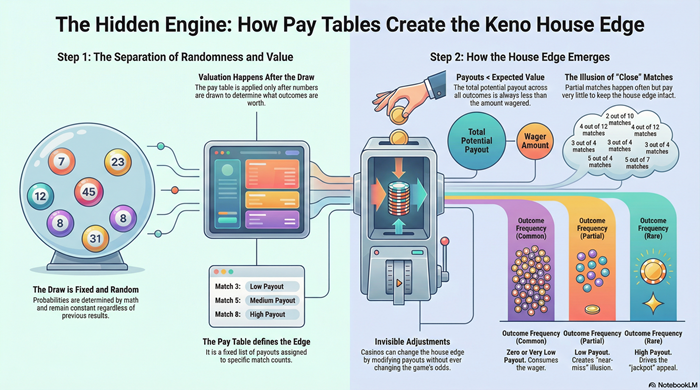

Crucially, no system can change the house edge created by the pay table. Even if a system altered hit frequency temporarily, it would not improve long-term return. Over enough draws, the same imbalance reasserts itself.

Why This Myth Is Especially Persistent in Keno

Keno produces constant numeric feedback. Every draw displays many numbers, partial matches, and near-misses. This creates abundant material for pattern interpretation.

Near-misses reinforce belief by making failures feel informative. Partial success is mistaken for progress. Repetition is mistaken for trend.

Because the game looks analytical, analytical-looking systems feel appropriate—even when they have no mathematical basis.

What Understanding This Changes

Understanding why systems fail does not require rejecting curiosity or discipline. It simply establishes a boundary between description and prediction.

Tracking can describe what has happened. It cannot improve what will happen next.

Once that boundary is clear, the appeal of systems weakens. Keno outcomes stop looking like signals and start behaving like independent random events evaluated against a fixed structure.

That clarity completes the picture. Odds define possibility. Pay tables define return. Variance defines experience. Near-misses define perception. Systems fail because none of these elements depend on the past.