How Roulette Really Works: Odds, House Edge, and Why Systems Fail

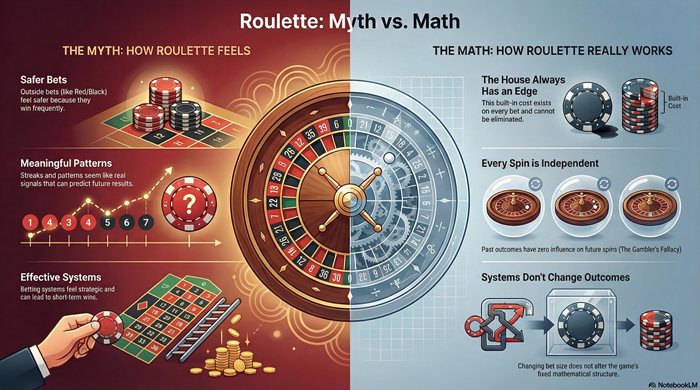

Roulette appears simple because its rules are simple. Bets are familiar, outcomes are visible, and wins occur often enough to feel validating. That surface clarity masks a game that is mathematically rigid and indifferent to player behavior.

Most misunderstandings about roulette come from confusing short-term experience with long-term probability. Streaks feel informative, certain bets feel safer, and timing feels meaningful. None of these perceptions alter how roulette actually works.

This guide explains roulette from first principles: how the wheel defines probability, where the house edge comes from, why outcomes never “correct,” and why betting systems fail regardless of logic or discipline. There are no strategies here—only structure.

What Roulette Actually Is (and Is Not)

Roulette is a fixed-probability game. Each spin produces exactly one outcome from a known and finite set of possibilities. Those probabilities are defined by the wheel and do not change in response to player choices or past results.

Roulette is often misunderstood because it combines randomness with visible mechanics. Seeing the wheel spin and the ball bounce creates the impression that observation or timing might matter. Visibility, however, does not create influence.

Roulette is:

- Governed by a fixed outcome space

- Defined by unchanging probabilities

- Fully specified before any bets are placed

Roulette is not:

- Adaptive to past results

- Self-correcting over time

- A puzzle with hidden states or exploitable rhythms

The game is complete before the first spin occurs. Nothing that happens during play alters its structure.

The Wheel Is the Game

Everything that matters in roulette begins with the wheel. The number of pockets determines the probability of every possible outcome. That structure exists independently of bets, players, or sessions.

Each spin selects one—and only one—pocket. Outcomes are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. Because the wheel defines the outcome space, it also defines the mathematical limits of the game.

This structure imposes several constraints:

- Probabilities are fixed by pocket count

- Payouts do not adjust dynamically

- Expected cost is locked in

- Player behavior operates on top of the system, not within it

Once the wheel and payout table are set, the mathematical behavior of roulette cannot be altered.

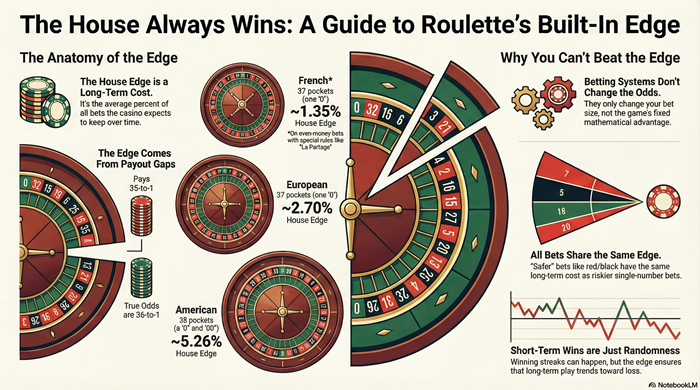

House Edge: Where the Cost Comes From

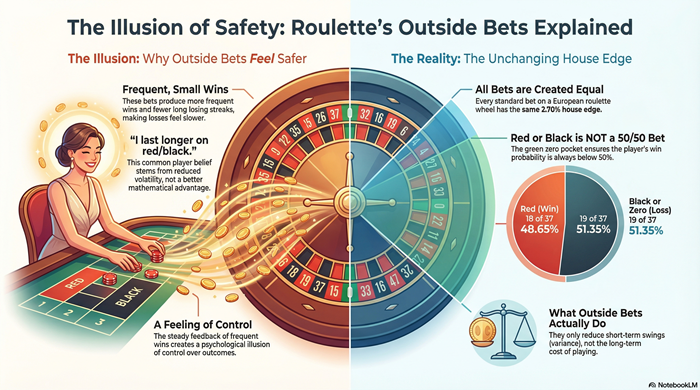

The house edge is the mathematical cost of playing roulette. It represents the average percentage of money wagered that the casino expects to retain over a very large number of spins.

This does not mean the casino wins every spin or that players cannot win in the short term. It describes long-run expectation, not immediate outcomes.

In roulette, the house edge exists because:

- Payouts are slightly lower than fair probabilities require

- Extra outcomes exist that are not fully paid for

- That shortfall applies to every wager

Crucially, the house edge is not tied to specific bets. All standard bets on the same wheel share the same expected loss. Bet selection changes variance, not cost.

For a deeper explanation of how this works in practice, see what the house edge in roulette represents.

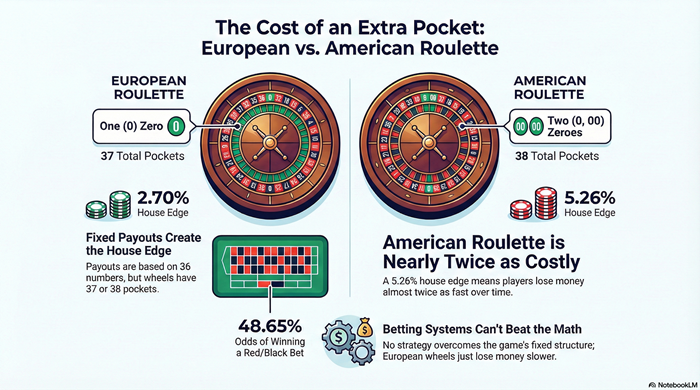

European vs American Roulette: One Extra Pocket, Permanent Impact

Roulette wheels are not identical. The difference between European and American roulette is subtle in appearance but significant in effect.

European roulette has:

- 36 numbered pockets

- One zero

- 37 total outcomes

American roulette adds:

- A second zero

- 38 total outcomes

Payouts remain the same on both wheels. Increasing the number of outcomes without increasing payouts raises the house edge—nearly doubling it on the American wheel.

This distinction means:

- European roulette is less costly to play

- American roulette extracts more per unit wagered

- Neither wheel becomes beatable

For a full breakdown of this structural difference, see

the difference between European and American roulette.

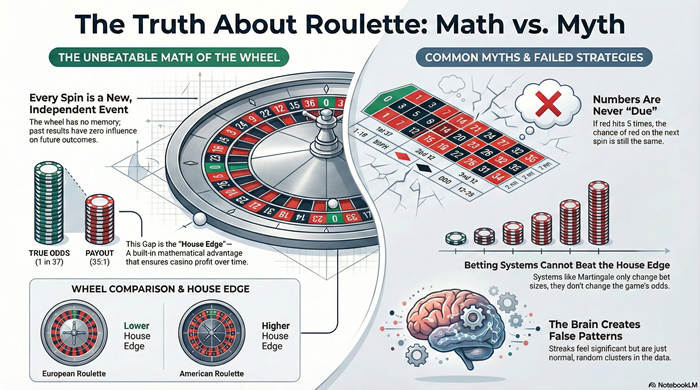

Independence: Why Every Spin Starts Fresh

Roulette spins are independent. Independence means each spin has no connection to any previous spin. Probabilities reset completely after every outcome.

In practical terms:

- The wheel has no memory

- Streaks do not influence future spins

- Numbers are never “due”

- Past frequency does not change likelihood

A number absent for hundreds of spins is no more likely to appear on the next spin than one that just hit. Tracking outcomes can describe history, but it cannot improve prediction.

This misunderstanding is formalized in the gambler’s fallacy in roulette.

Variance and Volatility: Why Results Feel Meaningful

If roulette is structurally fixed, why do player experiences differ so widely? The answer is variance.

Variance describes how much short-term results can deviate from long-term averages. In roulette, variance explains why players can win quickly, lose abruptly, or experience long streaks without contradicting expected value.

Volatility is how variance feels:

- High-volatility bets produce large swings

- Low-volatility bets produce smoother outcomes

- Both lose at the same expected rate

Short sessions are dominated by variance. Long sessions gradually reveal expectation. This is why

short-term roulette results feel meaningful even when nothing structural has changed.

Why Patterns Appear (and Why They Don’t Matter)

Roulette outcomes often appear patterned. Long runs, repeating numbers, and clustered results seem meaningful. These impressions arise from human perception, not from the wheel.

True randomness produces clusters and streaks naturally, especially in short sequences. What appears structured is often randomness behaving normally.

Patterns arise because:

- Random processes create streaks

- Short samples exaggerate structure

- Human cognition seeks order in noise

Patterns can describe what has already happened. They cannot predict what comes next, change probability, or alter expected value. For a deeper explanation, see why roulette patterns appear.

Can Roulette Be Predicted?

Roulette feels closer to prediction than many games because it is physical. Players can see the motion that leads to an outcome. That visibility invites the belief that outcomes might be anticipated.

In theory, roulette follows physical laws. In practice, it behaves as a chaotic system, where tiny, unmeasurable differences in starting conditions produce large differences in outcomes.

Prediction fails because:

- The system is highly sensitive to initial conditions

- Relevant variables cannot be measured precisely

- Small errors compound rapidly

- Each spin resets independence

Roulette is predictable only in the aggregate. Individual spins remain unpredictable. For more detail, see the limits of predicting roulette outcomes.

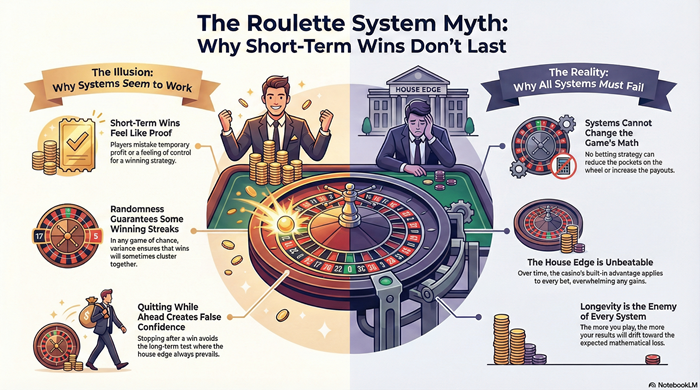

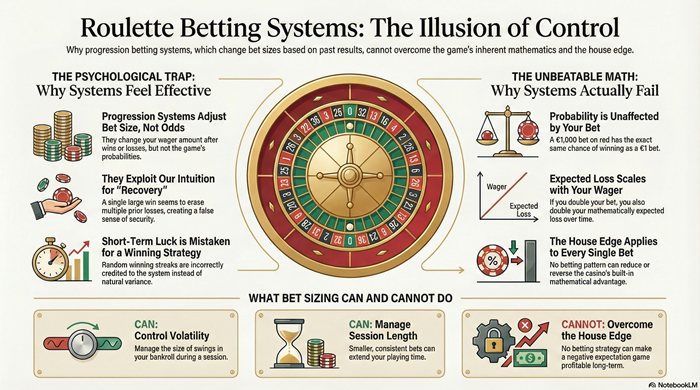

Why Betting Systems Don’t Change the Math

Betting systems adjust stake size, timing, or progression. They do not alter probability, payouts, or independence.

Systems can change:

- Volatility

- Emotional experience

- Session length

Systems cannot change:

- The number of outcomes

- Payout ratios

- Expected value

- The house edge

Short-term success under a system reflects favorable variance, not effectiveness. Over time, expectation dominates. This is why roulette systems don’t work long term.

Why Roulette Still Feels Beatable

Roulette feels beatable because it produces frequent wins, immediate feedback, and occasional short-term success.

Belief persists because:

- Even-money bets win often

- Short sessions can end positively

- Losses are unevenly distributed

- Success stories are remembered

The game feels responsive in the short term while remaining fixed in the long term.

What Understanding Roulette Actually Gives You

Understanding roulette does not create an edge. It creates clarity.

That clarity includes:

- Knowing why wins occur without advantage

- Knowing why losses accumulate over time

- Knowing why systems feel effective briefly

- Knowing why belief persists

Roulette becomes predictable in structure, not in outcome.

How This Guide Fits With the Rest of the Series

This page synthesizes the full explanation of roulette. Each supporting article isolates one concept—house edge, independence, variance, patterns, prediction, or systems—and examines it in depth.

For navigation across the full series, see the Roulette Education Guides.

What This Explanation Ultimately Shows

Roulette is not deceptive or adaptive. It is consistent.

Every spin operates under the same constraints:

- A fixed outcome space

- Fixed payouts

- Independence between results

- A permanent house edge

Short-term wins are real. Long-term losses are statistical. Systems fail not because they are poorly designed, but because they attempt to solve a game whose structure does not allow a solution.

Understanding roulette does not make it beatable.

It makes it intelligible.